When Caitlin Clark, a renowned player for the University of Iowa women’s basketball team, made a 3-pointer against the University of Michigan on February 15, 2024, she broke the NCAA women’s scoring record. Commentators pointed out that Clark had surpassed Kelsey Plum’s total of 3,527 points. However, it was rarely mentioned that there was still one more Division I women’s scoring record to beat, held by Lynette Woodard. Woodard scored 3,649 points while at the University of Kansas from 1978 to 1981, a record set before the NCAA offered women’s championships, when the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) was in charge. On February 28, 2024, during a game against the University of Minnesota, Clark surpassed Woodard’s AIAW milestone in the fourth quarter, bringing attention to this lesser-known chapter of sports history.

The AIAW was founded in 1972 and, within a decade, became larger than the NCAA, with nearly 1,000 member schools. It sponsored 19 sports across three divisions and was the only organization for women’s collegiate sports that was led by women. However, the AIAW was eventually overshadowed by the NCAA, in what SUNY Cortland sports management professor Lindsey Darvin describes as a “hostile takeover.” As a researcher focusing on sports, gender, and American culture, I examine the AIAW as a key but often overlooked moment in sports history, and I am writing a book about its philosophy, influence, and legacy.

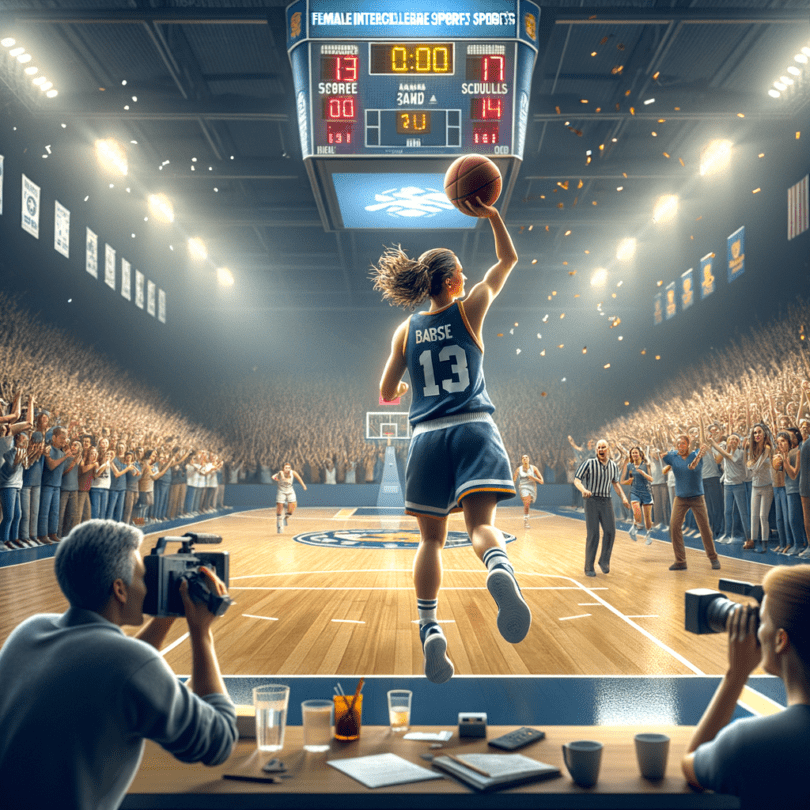

In the narrative of women’s sports in the U.S., Title IX is frequently discussed. This federal law mandates equal opportunities for female college athletes. However, the AIAW, an organization led by women that made significant changes in collegiate sports, is less frequently mentioned. Its governance model, centered around students, is still relevant today as college athletes push back against NCAA authority, using avenues such as transfer portals and deals for name, image, and likeness.

In the early 20th century, female college students primarily engaged in physical education focused on health and wellness, with few options for organized team sports. By the 1960s, however, women students began demanding the same school-sponsored intercollegiate teams and championships that men had. While supportive, women physical education professors were wary of the NCAA’s model of sport, rife with exploitation and scandal under what historians call the “cynical fiction” of amateurism. The AIAW arose from these demands, aiming to create an athletic governance organization directed by and for women, focusing on high-level competition and the welfare and education of student-athletes.

Under the AIAW, all teams and athletes received equal support without being singled out for their revenue potential. Athletes had rights to due process, an appeals system, and student representation on various committees. The association was funded by member schools and some advertising and media contracts. Women’s athletic programs were led by educators turned coaches and administrators. Many of the most renowned coaches in women’s basketball began with the AIAW, including C. Vivian Stringer, Pat Summit, and Tara VanDerveer, who recently set a record for most wins in college basketball. Other notable AIAW players include Ann Meyers-Drysdale, Nancy Lieberman, and Lusia Harris, who recently inspired an Oscar-winning documentary.

Title IX, enacted in 1972, significantly influenced the growth of women’s college sports, requiring equitable opportunities for both genders in educational activities, including athletics. This law was passed just before the AIAW’s first championship season, prompting calls for equitable resources for women’s sports. Initially, there was backlash from male-dominated sports organizations like the NCAA, viewing women’s sports as a threat to men’s sports. Despite fears, college sports continued to thrive. Over 50 years, although many schools have not fully complied with Title IX, none has lost federal funding due to violations. Title IX scholar Sarah Fields argues that without punitive measures, the law is limited. However, changes have resulted from complaints and lawsuits by students and administrators’ resolve to protect women’s athletic opportunities.

In the 1970s, most administrators supporting Title IX worked within the AIAW. By the late 1970s, clearer guidelines for Title IX compliance were established by the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The NCAA and AIAW couldn’t collaborate, so the NCAA shifted its focus to controlling women’s sports. In the 1981-82 school year, the NCAA offered women’s championships for the first time, using its resources to entice women athletes away from the AIAW’s unpaid championships. This led to a significant loss of AIAW members, causing it to close operations in 1982, despite women preferring its educational approach.

The NCAA made vague promises to enhance women’s athletics but offered limited representation on its governance boards. Female student-athletes then found themselves managed by a male-led organization. Gender inequity persists in the NCAA, with women holding 41.3% of head coaching positions for women’s teams and 23.9% of athletic director roles—positions once dominated by women under the AIAW. A recent gender equity review highlighted that the organization has historically underfunded women’s championships due to gender bias and profit motives. The NCAA and its corporate partners would have people believe their organization is central to college sports.